Introduction

The aquaculture of hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria) in Florida is a relatively young industry that has grown very rapidly over the past several years. Hard clams have notably few infectious diseases, compared to other bivalve molluscs, and to date no significant problems due to infectious diseases have been observed in cultured clams from Florida waters. There is a growing concern, however, that disease-causing agents may appear as production densities increase. Information provided in this document is intended to familiarize clam growers with common clam diseases.

Gross Signs of Disease in Hard Clams

Gross signs of infectious disease in juvenile or adult hard clams may go unnoticed because clams are infaunal; that is, living buried in the sediment. However, most diseased or stressed individuals will rise to the sediment surface. Additional signs of infectious disease in clams may include: gaping (inability to hold the valves closed); shell deformities or chipping of the shell margin; deposits or blisters on the inner surfaces of shells; excess mucus production; watery meats; dark, pale, or discolored meats; lesions or ulcers of the mantle, adductor muscle, or foot; or retracted and/or swollen mantle edges. These signs are not necessarily indications of infectious disease; they may also be associated with noninfectious diseases and adverse environmental conditions.

Types of Clam Diseases and Pests

Pathogens can potentially infect all life stages of hard clams. Organisms of particular concern include QPX (Quahog Parasite Unknown), which has caused significant mortality of cultured clams in northeastern states, and Perkinsus spp., an oyster disease which clams are known to carry, though they do not get sick. Other potential pathogens of M. mercenaria include common bacteria in the environment, such as Chlamydiales and Rickettsiales. It should be noted that none of these diseases affect humans.

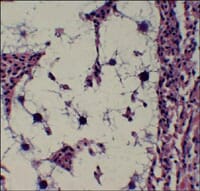

QPX

Figure 1. Photomicrograph of QPX, with "halo"-like area surrounding the parasites in hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) tissue. Figure 1. Photomicrograph of QPX, with "halo"-like area surrounding the parasites in hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) tissue.Photo by R. Smolowitz |

QPX, short for Quahog Parasite Unknown, is the only significant pathogen of hard clams. Significant prevalence of QPX, a "slime-net" protist, has been associated with clam mortality (up to 95%) from Canada to Virginia. QPX has not been detected in seed clams, suggesting that clams become infected in the planting areas. Observable signs of QPX include a retracted, swollen mantle edge and visible nodules in the tissue. Stained tissue sections are typically used to identify the QPX organism, which ranges from about 2 to 20 microns in diameter. A characteristic feature is a clear, "halo"-like area surrounding the parasite ( Figure 1 ). Moderate to severe infections result in slower growth and poor quality meat. Environmental factors contributing to the disease are still being clarified. QPX is apparently only found at high salinity sites (> 30 ppt). Mortalities have been primarily associated with additional stressors, including unusually low temperatures in northern states and very high-density culture.

Perkinsus spp. (Dermo)

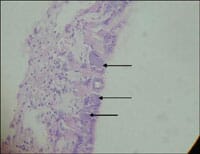

Figure 2. Photomicrograph of Perkinsus prezoosporangia in stained hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) digestive gland tissue. Figure 2. Photomicrograph of Perkinsus prezoosporangia in stained hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) digestive gland tissue.Photo by Jamie Holloway, 2003. |

Perkinsus spp. are protozoans that cause Dermo disease in eastern oysters, resulting in significant mortalities along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. Although Perkinsus spp. are sometimes found in hard clams, they apparently do not cause noticeable signs of disease in clams. In oysters, signs of Dermo disease include an increase in pigmented cells in the heart, occlusion of blood vessels, and ulcers of the mantle. High levels of infection result in cessation of growth, poor meat quality, and loss of adductor muscle strength. Perkinsus spp. are detected using Rays fluid thioglycolate medium (RFTM). Using this diagnostic technique, pieces of bivalve tissue are incubated in RFTM, allowing the parasites to enlarge. After several days, the tissue is removed from the medium and stained. The enlarged and stained parasites can then be easily viewed under a microscope ( Figure 2 ). Environmental factors contributing to the disease include high temperatures (>25°C) and moderate salinities (~ 13-28 ppt). The parasite appears intolerant of salinities below 9 ppt. Parasitism by blood-sucking snails and the presence of environmental contaminants may be contributing factors.

Chlamydiales and Rickettsiales

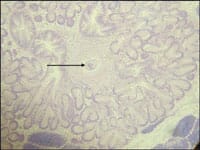

Figure 3. Photomicrograph of Rickettsiales-like organisms (arrows) in hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) gill. Figure 3. Photomicrograph of Rickettsiales-like organisms (arrows) in hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria) gill. Photo by Denise Petty. 2005. |

Chlamydiales and Rickettsiales are intracellular bacteria that are relatively common in bivalve molluscs. Although these parasites can cause localized damage to gills and epithelia, and infrequent mortalities, they are generally considered benign. Chlamydiales-like organisms (CLO) and Rickettsiales-like organisms (RLO) are identified by examining tissue sections for swollen cells filled with inclusion bodies, which result as the organisms proliferate ( Figure 3 ). Ruptured cells and tissue damage may also be observed. CLOs are usually found in the epithelium of the digestive gland, while RLOs are typically found in the gills. Both organisms are found more frequently in cultured bivalves than in wild stocks. Increased prevalence may be related to ease of transmission or increased stress on the host in high-density culture.

Pest Metazoans and Symbionts

Many marine organisms are occasional parasites or symbionts of clams. These can include parasitic nematodes (roundworms), cestodes (tapeworms), trematodes (flatworms), and copepods, which primarily enter clams through the walls of their digestive tracts. In addition, nemertean worms may be found as symbionts in mantle cavities. Usually, there are too few organisms to cause pathology or mortality. However, their presence in tissues may result in granulomas.

Granulomas

Figure 4. Photomicrograph of a trematode (arrow) in a granuloma within the digestive gland of a hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria). Figure 4. Photomicrograph of a trematode (arrow) in a granuloma within the digestive gland of a hard clam (Mercenaria mercenaria).Photo by Denise Petty. 2005. |

Granulomas are areas of thickened (fibrotic) tissue resulting from the clam's immune response to a foreign body, including any of the parasites listed above ( Figure 4 ). Blood cells called granulocytes, which are part of the clam's immune system, migrate to and infiltrate the area surrounding the parasite (inflammation - tissue response to injury or infection of tissues, which serves to destroy, dilute, or wall off the injurious agent and the injured tissues). These cells may eventually encapsulate the parasite, forming an inflammatory lesion, or nodule, called a granuloma. Granulomas are detected by examination of tissue sections. The number of granulomas is usually too low to cause impairment of function, but if present in greater numbers, causative agents should be identified or ruled out, and further investigation may be warranted.

Significance in Florida

Florida cultured clams were examined for disease in February (winter) and August (summer) of 2003 using histology and RFTM. Three areas were monitored to represent the majority of clam production areas in Florida; northwest coast, east coast, and southwest coast. The Gulf Jackson High-Density Lease Area (HDLA), located in the inshore waters of the Gulf of Mexico, near Cedar Key, FL was sampled in both winter and summer. The Indian River Aquaculture Use Zone located in the Indian River, near Sebastian, FL, was also sampled in both winter and summer. Southwest Florida samples were taken at two different sites. Winter collections were taken from the Sandfly Key HDLA, near Placida, FL. Summer collections were taken from the South Pine Island HDLA, located in Pine Island Sound, near St. James, FL. Clams were collected by participating growers from culture bags that were being harvested for market. Live clams were shipped to the University of Florida, Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences (UF-FAS), in Gainesville, FL. Samples of 60 clams, each, were divided equally between preparation for histology and RFTM.

In the group of clams examined, granulomas were the most frequently observed abnormality, followed by Rickettsiales-like organisms, non-granulomatous inflammation, and metazoans (Table 1 ).

There was no evidence of QPX in cultured clams from the three areas that were examined as part of this study. While QPX has never been identified in Florida clams, there is concern that it could be introduced to the state. Consequently, imported clams and oysters must be tested and proven free of the QPX agent before entry into Florida, as per Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Division of Aquaculture best management practices.

|

Table 1. Percentage of affected clams from seasonal collection sites in Florida.

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growing Site | Season (2003) | QPX | Perkinsus | Rickettsiales | Metazoans | Granulomas | Inflammation |

| NW FL | Winter | 0% | 0% | 60% | 0% | 13% | 20% |

| Summer | 0% | 23% | 0% | 7% | 40% | 7% | |

| East FL | Winter | 0% | 0% | 47% | 17% | 30% | 0% |

| Summer | 0% | 7% | 13% | 23% | 20% | 3% | |

| SW FL | Winter | 0% | 3% | 33% | 27% | 40% | 67% |

| Summer | 0% | 67% | 0% | 0% | 53% | 10% | |

Perkinsus was identified in clams from all three study sites tested during this study. With the exception of one animal collected in the Southwest Florida area, all Perkinsus positive clams were collected during the summer sampling period. In total, 23% of the clams collected at Gulf Jackson, 7% from Indian River, and 67% from southwest Florida were affected. When Perkinsus is seen in clams, it is indicative of an adjacent population of infected oysters. Oysters are susceptible to infection by P. marinus, and there are many strains varying in infectivity. Therefore, although hard clams do not develop disease from Perkinsus infection, they can serve as vectors for the organism. Moving infected clams from one geographic location to another may introduce a new strain of Perkinsus to oysters and other susceptible bivalve molluscs.

Rickettsiales-like organisms were observed in the gills of clams collected in the winter from all three areas; 33% to 60% of the clams sampled had RLOs, with the greatest prevalence at Gulf Jackson. In the summer, only clams from the Indian River had RLOs (13%). Where RLOs were present, adjacent branchitis (gill inflammation) was infrequently observed. It is unclear if the RLOs are a significant problem for the clams. No Chlamydiales-like organisms were observed in any of the clam samples.

Granulomas were the most frequently observed abnormality in the examined clams. Southwest Florida clams, regardless of season, were more affected than clams from the other collection areas. However, clams from all sites and seasons were affected. Prevalence of granulomas ranged from 13% (Gulf Jackson winter collection) to 53% (summer Southwest Florida collection). Metazoans, usually trematodes, were observed in some of the granulomas; up to 26% of the clams from a single collection were affected.

Non-granulomatous inflammation is a cellular response by an animal to a non-specific (unknown cause) injury. Non-granulomatous inflammation was observed in 66% of the winter-collected clams from the Southwest Florida area, with much less observed in clams collected in other sampling sites and seasons (less than 20%). The source(s) of the non-granulomatous inflammation was not determined.

Summary

To date, no significant problems due to infectious diseases have been identified in cultured clams from specific locations in Florida waters using histology or RFTM. Clinical disease caused by infectious disease was also not observed during the survey period. Our survey, therefore, suggests that, at present, there are no serious disease-causing agents associated with clams at the locations we examined. Although Perkinsus spp. was found, sometimes in relatively high numbers, it is a disease of oysters and has not been associated with clinical disease in hard clams. QPX, the clam pathogen of most concern, was not found. Granulomas, Rickettsiales-like organisms, non-granulomatous inflammation, and metazoans were found to varying degrees. In general, these were considered incidental and not significant; numbers were too low to cause pathology or mortality.

Most of these potential disease-causing organisms are present in the environment and are therefore difficult to control. Pathology may be exacerbated by stressors such as high temperatures (> 30°C), poor water quality (presence of noxious algae or contaminants, low dissolved oxygen, etc), or high stocking densities. There is a growing concern that the tendency to increase production and standing crop is conducive to the accidental introduction of disease-causing agents or increased stresses that may facilitate disease by these typically opportunistic organisms.

Clam culture in Florida currently is dependent on monoculture of one species, Mercenaria mercenaria. One of the great risks associated with monoculture is the potential for catastrophic loss following the appearance of a new disease-causing agent. In order to minimize risk and potential economic impact on the industry, growers should be aware of potential shellfish diseases and be prepared to properly assess any occurrences of diseases. Assistance from UF/IFAS Extension shellfish and aquatic animal health specialists is available.

May 2007